The Myth of Musk: How Elon Conned the World

The Superhero Origin Story the World's Richest Man Doesn't Want You to Know

I’m going to tell you two stories.

The first story is a rags-to-riches tale about a billionaire super-genius you may have heard of by the name of Elon Musk.

This is his backstory:

Musk was born in South Africa to working-class parents, and young Elon showed such an aptitude for computer programming that he created and sold his first piece of software at the ripe age of 12, garnering the attention of several Ivy League schools in America.

Elon accepted an invitation to attend the University of Pennsylvania, where he double-majored in physics and economics before going on to Stanford for a PhD in applied physics.

After getting his PhD, Elon and his younger brother, Kimbal, founded and bootstrapped a novel software company called Zip2 from scratch, eventually selling it to Compaq Computers for more than $300 million.

Elon used the proceeds from Zip2 to found PayPal, bringing the same level of work ethic and computer brilliance to his newest endeavor. Before long, eBay came calling and purchased PayPal for $1.5 billion. Now that he was what you might call “filthy rich,” Elon could finally afford to sit around inventing, designing, and building whatever science-fiction toys struck his fancy.

First up was an ambitious space exploration company known as SpaceX, created with the goal of reducing space travel costs with reusable rockets and enabling human colonization on Mars.

Musk followed that with the creation of a novel, electric self-driving car company called Tesla—fittingly named after Nikola Tesla, widely regarded as one of the most brilliant inventors in modern history. In the grand pecking order of genius inventors down through the ages, it was basically: Leornardo Da Vinci, Sir Isaac Newton, Tesla (and his chief rival, Thomas Edison), Tony Stark (a fictional character), and then Elon Musk, who was the closest thing planet Earth had to a real-life Avenger.

Hell, all Stark’s AI program J.A.R.V.I.S. could do was operate the Iron Man suit and make cappuccinos. Elon’s was going to control every car on the road in the very near future and integrate with a computer chip he was going to implant directly into people’s brains. Neuralink was born. (Seriously, who needs a fictional Tony Stark when the world has a very real Elon Musk!)

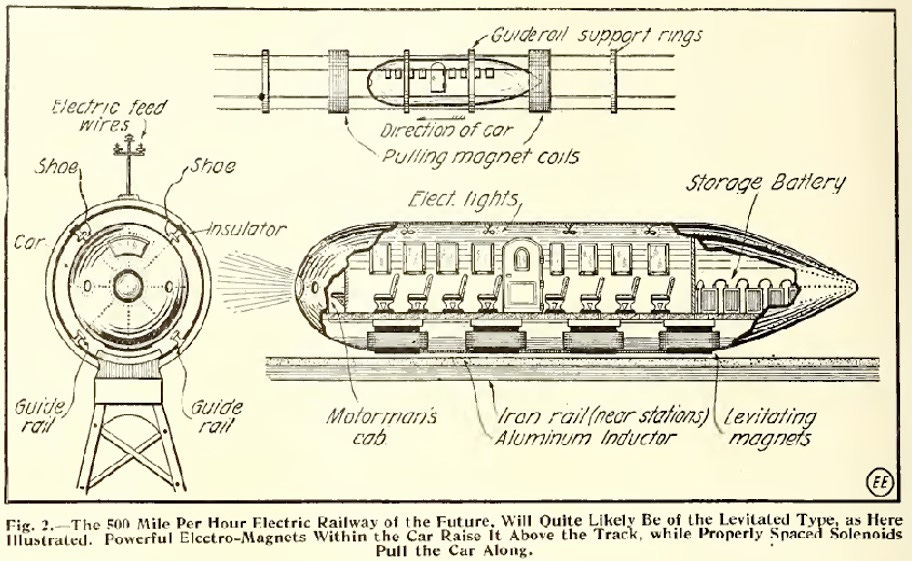

In 2013 he came up with the Hyperloop—a nearly supersonic transportation system using magnetic propulsion and capsules situated inside a low-pressure tube system (think those bank canisters at the drive-thru teller).

Then in 2015 he came up with Starlink, a series of satellites aimed at providing broadband internet to the entire globe.

In 2017 he came up with the Boring Company, a revolutionary tunnel-digging infrastructure endeavor intended to solve traffic congestion with a maze of underground tunnels.

Then he bought Twitter and rebranded it as X.

Then he built his own AI model, Grok, to compete with ChatGPT.

In 2021, Elon Musk was fittingly named Time magazine's Person of the Year, months after becoming the world’s richest person.

In some corners of the internet, it was even rumored that Elon Musk might, in fact, be an alien, sent to earth from the distant heavens to guide humanity and usher in the next golden age of human development…out among the stars.

And so, it made perfect sense for the world’s richest man—justifiably so through a series of self-actualized, staggeringly ambitious, cutting-edge inventions that only the most gifted of minds could conceive, let alone deliver, each one more impressive than the last—to be tapped by the President of the United States of America to bring his Ivy League credentials, impeccable business acumen, other-worldly outside-the-box thinking, and pull-yourself-up-by-your-own-bootstraps approach to solve everything that ails our government.

If a poor kid from Africa could set out on his own to build a freaking interplanetary business empire entirely from scratch with nothing but his wild imagination, superlative intellect, and can-do attitude to become the wealthiest «ahem» “human being” in the history of our planet, surely we should turn him loose on the inefficient, broken, malodorous cesspool that is Washington!

After all, this was the guy who said in an interview with The New Yorker way back in 2009, “The likelihood of humanity gaining a true understanding of the universe is greater if we expand the scope and scale of civilization and have more time to think about it. We’re like a giant parallel supercomputer, and each of our brains runs a piece of the software.”

Whew!

Mind. Blown.

The likelihood of humanity gaining a true understanding of the universe is greater if we expand the scope and scale of civilization and have more time to think about it. We’re like a giant parallel supercomputer, and each of our brains runs a piece of the software.

I mean, if what’s wrong with America can’t be fixed by Elon Musk, it can’t be fixed at all.

So the question, dearest earthlings, is why any sensible person would not want to hand over the reins of our fallible, inefficient, spectacularly stupid government to this [possibly extraterrestrial] once-in-a-century super-genius? What could it possibly harm?

In case you already forgot, I said at the beginning I was going to tell you two stories.

The first story I just told you was the Elon Musk origin story I knew and loved for the better part of 20 years. And if it all sounds a little too good to be true, that’s because it is.

This second story is also the Elon Musk story.

The REAL Elon Musk story…

Would the Real Elon Please Stand Up

“Some people are born on third base and go through life thinking they hit a triple.” - Barry Switzer

Musk was indeed born in South Africa, but it was to a supermodel mother and a [former politician] engineering consultant father who built office buildings, retail complexes, an air force base, owned an auto parts store, and—if you believe Errol Musk’s account—had at least a partial stake in an emerald mine in Zambia. According to a Musk biographer, the family lived in “the largest house in Pretoria.”

Young Elon did show an early aptitude for computer programming and did indeed sell a video game he created at the age of 12 for $500 (It was called Blastar, and you can actually play the original game he built in 1984.), though there is no record of any American school, Ivy League or otherwise, having any knowledge of the small bit of code published in a magazine on the other side of the world.

Elon’s parents divorced when he was 8, and at the age of 17 he encouraged his mother, Maye, to regain her Canadian citizenship since she’d been born there. Maye obliged, and as soon as she obtained a Canadian passport, Elon applied for one as well. Having recently graduated from high school, Elon decided to move to Canada to be closer to where he ultimately wanted to land—the United States.

Maye bought him a one-way ticket, gave him money to live on, and the name of a cousin in Saskatchewan. She joined him a few months later with his little sister, Tosca, while Kimbal stayed in South Africa to finish high school.

Elon first attended Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, before transferring to the University of Pennsylvania in 1992, where he earned a Bachelor of Science in Economics and a Bachelor of Arts in Physics. He was accepted to a PhD program for materials science at Stanford in California but dropped out after just two days to focus on his first entrepreneurial venture, Zip2.

Unfortunately, this is where the real story begins to diverge from the myth rather significantly.

Zip 2

Zip2 was a concept Elon “came up with” during a summer internship in 1994 when a Yellow Pages salesman came into his employer’s office to pitch an online business listing on this brand new “internet” thingy in addition to the traditional phone book listing. Elon heard the pitch and thought to himself, That sounds like a great idea—I should borrow it and create my own version, which is what he did.

Initially called Global Link Information Network, Elon, Kimbal, and a friend named Greg Kouri started the company together in 1995 with money raised from a small group of angel investors. Plus $8,000 of Kouri’s money. Plus $10,000 of his mom’s money (Maye was also financially supporting both boys at the time since neither had a job). Plus (depending on who you ask) $28,000 of his dad’s money (Ashlee Vance’s 2015 biography of Musk claims Errol chipped in $28K, which Elon denied, then later added that his dad chipped in 10% of a $200k seeding round). Whether the full amount Errol gave the boys was $28K or closer to $20K, he remains adamant that money came from the emerald mine.

In 1996, Global Link officially changed its name to Zip2 after receiving a $3 million investment from Mohr Davidow Ventures, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm. But that $3 million came with a catch: Mohr Davidow insisted on bringing in their own leadership—like CEO Rich Sorkin—and a new software engineering team to rewrite Elon’s code. If Elon wouldn’t mind going and standing off to the side, thank you very much, the professionals would take it from here. As a consolation prize, he could put Chief Technology Officer on his business card.

In 1999, after three years of standing off to the side, Compaq Computer paid $305 million to acquire Zip2—netting Elon $22 million for his share—and proving to the budding entrepreneur that with the right attitude, someone else’s idea, someone else’s startup money, someone else’s seed money, someone else’s venture capital, someone else’s leadership, someone else’s software engineering know-how, and mom and dad paying all the bills, anyone can build a successful tech company.

X.com (AKA: The “Invention” of PayPal)

Elon used $12 million from the sale of Zip2 to start his next endeavor—an online banking platform called X.com. Greg Kouri once again put up a sizeable investment as well, and former Intuit CEO Bill Harris came aboard as the inaugural CEO, officially launching in December 1999.

The fledgling company amassed over 200,000 users within two months, possibly having to do with Elon paying customers $20 for each new member referral and another $10 for each new sign-up.

In Jan 2000, a massive—borderline farcical—security flaw was discovered in Musk’s new platform: any X.com user who had the bank account and routing number of any other bank account—even at other banks—could transfer money from that account into their own and then withdraw it, a feature known in corporate finance parlance as “HOLY S*** ARE YOU F****** KIDDING ME?!!!!”

In March 2000, X.com merged with its chief rival, a software company across town called Confinity. Co-founded in 1998 by Peter Thiel, Max Levchin, and Luke Nosek, Confinity had already developed and launched an online payment system of their own called Paypal that allowed users to send money to each other via PalmPilots.

Following the merger, the new company decided to shift focus off the banking aspect of Musk’s X.com to the payment aspect of Thiel’s Paypal. They changed the company name to PayPal, and Musk, as its largest shareholder, was appointed CEO.

By mid-2000, PayPal’s user base had exploded to over 1 million users, resulting in frequent outages and slowdowns, which were largely blamed on the Windows servers Elon had built his code on. The team decided to rewrite the code on the Unix platform the Confinity team used to build PayPal to handle the rapid scaling requirements, prompting pushback from Musk, who insisted his system could scale with the right tweaks.

The engineering team wasn’t buying it.

In October 2000, while Elon was off vacationing on his honeymoon, the PayPal board of directors, citing mismanagement, voted to oust Musk as CEO and replace him with Peter Thiel. Under Thiel’s direction, PayPal scrapped Elon’s original code for the much lighter and more flexible Unix-based system. The new system proved so robust and profitable that eBay decided to purchase PayPal in 2002 for $1.5 billion.

Though fired from the company, Elon retained his 11.7% stake and netted $175 million in the sale.

If you’re wondering why Elon is the name most associated with the creation of PayPal—despite having much less to do with it than nearly anyone else involved—it’s because of a clause he insisted be included in his separation agreement when he was removed as CEO that stated he was legally required to be referred to as “one of PayPal’s founders.” Nobody else on the PayPal team cared enough to make their founding status a legal issue.

If the Zip2 experience showed him just how far he could run with someone else’s ideas and capital, the PayPal experience convinced Elon that the sky was the limit if one could somehow put up a majority stake and retain ownership in someone else’s Big Idea.

With ownership kind of money in the bank, Elon could now focus his attention on a childhood pipedream: outer space.

SpaceX

In May 2002, Elon used $100 million of his PayPal money to launch Space Exploration Technologies Corp., with the ultimate goal of making humanity a multiplanetary species, and a particular focus on colonizing Mars. Believing the exorbitant cost of spaceflight was the biggest barrier to this vision, Elon aimed to drastically reduce those costs by developing reusable rocket technology.

There was just one issue: Elon had no idea how to develop reusable rocket technology—his entire vision began and ended with “Let’s go to Mars…for CHEAP!”

That was it.

Elon was about to discover that knowing what to do and knowing how to do it are two completely different beasts.

If you’re Leo Da Vinci, you sit down and sketch out a flying machine.

If you’re Nikola Tesla, you grab a screwdriver, wrangle a lightning storm, and build an energy teleportation device in your freaking barn.

If you’re Tony Stark, you start welding together Taliban scrap metal.

If you’re Elon Musk, you open your checkbook, hire rocket design expert Tom Mueller—a 15-year veteran in the propulsion and combustion department at aerospace company TRW—and tell him, “Mars…you go figure it out.“

From 2006 to 2008, SpaceX attempted three launches of rockets Mueller and his engineering team designed and built in-house, each of which resulted in “rapid unplanned disassembly,” flight-speak for “they done exploded.”

Teetering on the verge of bankruptcy, Elon used his last $30 million from the PayPal sale to fund a fourth launch, describing it as an all-or-nothing gamble.

The gamble worked.

Mueller’s Falcon 1 rocket design successfully launched in September 2008, becoming the first privately developed liquid-fueled rocket to reach orbit. And with that success, private investors began climbing aboard. Founder’s Fund, a venture capital firm co-founded by Peter Thiel, invested an estimated $20 million. Draper Fisher Jurvetson contributed another $40-50 million.

But the biggest windfall came courtesy of NASA, awarding SpaceX a $1.6 billion contract to deliver cargo to the International Space Station. By 2012, SpaceX had raised another $1 billion from private investors like Google and Fidelity.

In 2015, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 became the first rocket to launch…and successfully return for reuse…all thanks to the engineering brilliance of Hans Koenigsman.

By this point in time (as we’ll see in a minute), Elon was completely immersed in his own hype, rarely missing an opportunity to add to his mystique with laughably tall tales about his own prowess that the public—still imagining him to be Tony Stark incarnate—lapped up.

At an International Astronautical Congress conference in Adelaide, Australia, in 2017, Elon told a room full of doe-eyed worshippers, “We started off with just a few people who really didn’t know how to make rockets. And the reason I ended up being the chief engineer or chief designer was not because I wanted to, it was because I couldn’t hire anyone. Nobody good would join. So I ended up being that by default.”

Tom Mueller and Hans Koenigsman would no doubt be surprised to hear that.

It was at this very same talk that the crowd got a small taste of another marketing gimmick Elon was developing an affinity for: The Grandiose Pie-In-The-Sky Promise That Was Lightyears From Reality. In this case, it had to do with Mars.

Elon revealed to the conference-goers his plans for getting cargo rockets to Mars by 2022, followed by a crew in 2024. As of 2025, it’s looking more like 2035 at the earliest.

That’s not to say SpaceX isn’t a massive success—it most definitely is. Valued today at around $350 billion—the most valuable private company in the world—it’s not going anywhere anytime soon. (including Mars «snort»)

But it’s also not quite the visionary company Elon would have everyone believe. NASA already had the ability to launch rockets and the goal of eventually going to Mars. SpaceX’s engineers figured out how to spend less money on the launches by having the rockets come back, which isn’t actually the technology we need to get to Mars.

Elon’s biggest contribution to this whole endeavor seems to be little more than opening his checkbook, yelling at everyone to work harder, and then appearing at conventions in aviator shades and a bomber jacket to boast about personally inventing space travel.

On the other hand, perhaps Elon Musk is a testament to what one man can achieve. That is, when the federal government hands you $22.6 billion in contracts, loans, subsidies, and tax credits so you can hire the best and brightest to design you that Thing you want.

Speaking of hype and stolen valor…

Tesla

Elon Musk founded Tesla Motors in 2003.

Sorry, some habits die hard. Let’s try that again.

Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning founded Tesla Motors in 2003. At a time when EVs were largely seen as impractical or niche, the duo aimed to create ones that could compete with gasoline-powered cars in performance and appeal.

Eberhard was frustrated with the auto industry’s lack of progress on sustainable transportation. After GM recalled and destroyed its EV1 electric car in the late 1990s, he saw an opportunity to fill the gap. Tarpenning joined him to turn the vision into reality. Both men were engineers and successful entrepreneurs, with Eberhard serving as CEO and Tarpenning as CFO and Vice President of Electrical Engineering.

In 2004, Tesla did a Series A investment round to raise $6.5 million, and that’s how Elon Musk came to be involved. Musk put up $6.3 million himself and became chairman of the board. But while Eberhard and Tarpenning were content to just build better EVs, Elon’s vision for the company was to “help accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.”

While transitioning to sustainable energy is definitely a noble goal worth celebrating by tree-hugging Libs, Elon’s biggest contributions to Tesla had the precise opposite effect.

For starters, while Tesla as a company has over 3,000 patents, Elon is only listed as a co-inventor on one of them: a design patent for the charging connector. While EV chargers all had a universal shape, Tesla opted to go with a unique design. It didn’t charge the vehicles faster, or make the charges last longer, or do anything useful at all other than ensure that Tesla charging stations wouldn’t work on any other EV on the market. Obviously, this did nothing to aid the world’s transition to renewable energy.

Worse, Elon was insistent that Tesla focus on developing lithium-ion batteries rather than use the nickel-metal hydride ones everyone else was using. While lithium-ion batteries performed better, they came with a special requirement: mining lithium, a highly destructive environmental operation. So, while Elon’s head was in the right place pursuing EV technology to save the planet, the ecological destruction from Tesla’s dependence on lithium extraction cancelled out whatever benefits their electric cars delivered.

In 2006, Eberhard and Tarpenning gave an interview to the NY Times in which the Tesla founders made a horrible mistake: while discussing the new car they had been developing, they neglected to mention Elon Musk—the private investor who hadn’t helped them develop it.

Musk was furious.

He threatened to leave Tesla if Eberhard and Tarpenning didn’t contact the Times and demand a retraction or amendment to the article with a mention of himself. Recognizing an entitled-toddler-tantrum when they saw one, both men declined, further enraging Elon.

Seeing the immense potential of the company Eberhard and Tarpenning had built, Elon decided it would be super cool if he were the face of it instead and began the process of pushing Eberhard out.

In 2007, Elon orchestrated the firing of Eberhard, spitefully withholding the man’s severance pay on the way out. He anointed himself the new CEO and began publicly referring to himself as the “founder” of Tesla, prompting Eberhard to file a libel lawsuit against Musk, leading to a countersuit back at Eberhard claiming he was responsible for Tesla’s financial woes.

The two men reached a settlement out of court in 2009 for an undisclosed amount to Eberhard and a clause stipulating that Elon Musk could legally call himself a “founder” of Tesla.

With the actual founder out of the picture and the new “founder” now allowed to claim whatever title he wanted without threat of a lawsuit, Tesla still faced a major problem: they were way behind on production and they were almost out of money.

Enter the U.S. Government

In 2010, the Department of Energy—the same one Elon Musk’s rogue DOGE agency is attempting to dismantle—bailed Tesla out with a $465 million low-interest loan, allowing them to build their production facility in Fremont, CA, and launch the Model S sedan.

Beyond that initial loan, Tesla has received more than $10 billion domestically in government loans, tax credits, subsidies, and incentives; land and loans worth more than $2 billion from the Chinese government for the Shanghai Gigafactory; and over $10 billion in subsidies and tax breaks from Germany’s government for the Berlin Gigafactory. (In case anyone was wondering why Elon is so fixated on the politics of both countries and America’s foreign policy towards them)

With enough “nanny-state” government handouts to keep the company he didn’t create afloat, Elon Musk could finally unleash his “particular set of skills” and do what he did best: hype the everloving sh** out of his products with a bunch of wild promises that he absolutely couldn’t deliver. For example:

Self-Driving Cars – In 2016, Elon promised that Teslas would be fully autonomous within a year, capable of driving from Los Angeles to New York without human intervention.

Affordable Model 3 – In 2016, Elon promised that Tesla would produce a mass-market Model 3 priced at just $35,000 for the average consumer. In 2019, Tesla briefly rolled out a stripped-down version of the vehicle that had been promised, though it was almost impossible to get one, and then discontinued it.

Cybertruck – In 2019, Elon unveiled the Cybertruck, claiming it would be bulletproof, could tow more than the Ford F-150, and would revolutionize the entire pickup market—by 2021. After years of delays, the Cybertruck arrived in 2023 without the promised power or features—but with a heftier price tag. In March, Tesla recalled nearly every Cybertruck in America—its 8th recall—because the “bulletproof” panels were attached with faulty glue and kept blowing off driving down the highway. (And who can forget this spectacular fail):

Robotaxi Revolution – In 2019, Elon announced that Tesla would have 1 million robotaxis on the road by 2020, completely eliminating the need for human drivers and revolutionizing ride-share programs. As of April 4, 2025, no Tesla robotaxis exist.

So, while Tesla has done its part to evolve the EV market, it’s almost as well-known for its late deliveries, recalls, failed promises, unfulfilled hype, and spontaneously bursting into flames. In terms of its price-earnings (P/E) ratio, its stock has spent years vastly overpriced—largely due to Musk’s presence and the sham mystique he’s built for himself, inducing casual investors to FOMO into anything with his name attached to it.

The one area where it’s actually delivered on its promises—aesthetics—is all thanks to guys who aren’t Elon Musk: The original 2008 Tesla Roadster was built on a Lotus Elise foundation and adapted by Tesla’s early team of Malcolm Powell and Martin Eberhard. Later Tesla models are the brainchild of Franz von Holzhausen.

And getting $23 billion from the government never hurt anyone.

Hyperloop

By 2010, Elon Musk’s sterling reputation as an otherworldly Übermensch tech genius was cemented in the public psyche. Between PayPal, SpaceX, and Tesla, the Tony Stark comparisons were so ubiquitous and unavoidable that Hollywood was literally using Elon to validate Iron Man himself.

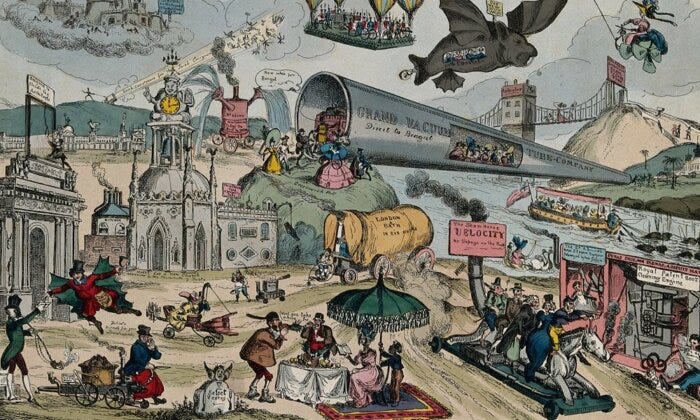

And just in case there were any lingering doubters on the planet as to Elon’s status in the echelon of Earth’s greatest minds, he was about to win over the last of them with the 2013 unveiling of his greatest invention to date—and one of the most scientifically advanced, cutting-edge inventions in human history: The Hyperloop.

Musk published a white paper in 2013 that boldly asked: Is there truly a new mode of transport—a fifth mode after planes, trains, cars, and boats—that also meets the criteria of being:

Safer

Faster

Lower cost

More convenient

Immune to weather

Sustainably self-powering

Resistant to Earthquakes

Not disruptive to those along the route

His paper concluded that indeed there was: it was a transportation system made of vacuum-sealed tubes, in which hollow capsules resting on a cushion of air used magnetic propulsion to travel at speeds in excess of 700 mph.

“THAT SETTLES IT—ELON MUSK IS OFFICIALLY THE TONY STARK OF THE NON-MARVEL UNIVERSE!” shouted most of humanity. “THIS IS STRAIGHT OUT OF A SCIENCE FICTION MOVIE!” they continued screaming at each other in all caps. “ONLY THE MOST BRILLIANT MIND IN EXISTENCE COULD INNOVATE SOMETHING OF THIS MIND-BLOWING MAGNITUDE!!!” they roared in unison, shaking their fists at the heavens and causing quite a scene at Applebee’s.

In case you haven’t picked up on the theme of this article yet, all was not as it seems.

For starters, here’s what most people in the general public didn’t know:

The Hyperloop concept had been around for at least 200 years, first championed by English clockmaker and inventor George Medhurst in 1810.

Ungodly amounts of money had been poured into the project over the years, with nobody coming anywhere close to figuring out how to make it work.

Elon Musk was more than happy to let the general public think he’d come up with this “revolutionary” concept that was two centuries old—it fed into his ever-growing lore. But even folks in Silicon Valley and the venture capital space had drunk enough of the Elon Kool-Aid by this point to think the Musk Rat really could succeed where everyone before him had failed.

On the strength of Elon’s name alone, Hyperloop raised nearly $450 million from investors that included Richard Branson and the Emirati port operator Dubai Ports World.

Unfortunately, that’s about where this portion of the story ends. Elon and the best minds his money could hire couldn’t figure out how to make it work either. They built a single prototype and a short bit of track at their California facility, and in 2020, they conducted their one and only test with human passengers.

It topped out at 107 mph.

The best and brightest engineering minds on the project concluded that nobody involved had truly grasped the full extent of all the problems that needed to be solved to make this technology work, and once they understood the problems they were dealing with, they realized they didn’t have the know-how or finances to solve them.

So, no, Elon Musk did not “invent” the Hyperloop.

The Hyperloop is not a thing that currently exists. It’s a concept from 1810 that Elon, like so many others, tried and couldn’t make work. At this point, Elon has effectively abandoned it, though other companies have taken up the mantle with more realistic goals and a bit more success.

Last year, the UAE announced a 1,200-mile underwater high-speed train linking Dubai and Mumbai, though it’s still just in the concept phase.

The Hyperloop TT Company has several test projects in the works in France, Italy, Brazil, and the U.S.

As these projects have already met with more success than anything Elon managed to achieve, industry insiders began revisiting a long-held, science-fiction pipe dream of a 3,000-mile tunnel connecting New York to London. But assuming the technology problem has actually been solved (it hasn’t), experts pegged the price for such a project at $20 trillion.

Ever the outrageous hype man, Elon immediately stepped up and declared he could build it for $20 billion—a staggering 99.9% cheaper!

Unfortunately for Iron Man Musk, his Hyperloop is all hype and no loop.

The Boring Company

In 2016, Elon Musk was stuck in Los Angeles rush-hour traffic, frustrated at the gridlock, and thought, I could solve all this stupid congestion with a series of underground tunnels! and tweeted out, “Traffic is driving me nuts. Am going to build a tunnel boring machine and just start digging…“

While casual readers may see this as the groundbreaking ingenuity of a once-in-a-generation hyper-intellect at work, savvier readers may recognize this as LITERALLY THE EXACT THOUGHT EVERYONE WHO HAS EVER SAT IN TRAFFIC AND/OR IS 6 YEARS OLD HAS HAD MULTIPLE TIMES A WEEK EVER SINCE THEY BEGAN DRIVING AND/OR TURNED 6.

It’s not a novel concept, is what I’m getting at.

The difference between you or me (or a 6-year-old) and Elon Musk is that Elon has hundreds of billions of dollars to go throw at someone to build whatever 6-year-old idea pops into his head on the 405, whereas you and I have to think about mortgages and car payments and the mounting emu softball gambling debts like regular people.

In 2017, Musk founded The Boring Company (TBC) as a side project under the SpaceX umbrella and began digging its first test tunnel on SpaceX’s property in Hawthorne, CA. Since it was on private land, it required few permits. And while digging, Elon unveiled his grandiose plans: the tunnels would incorporate the Hyperloop concept he’d envisioned—ingeniously just called “the loop” (since it was underground?)—with a transport system that could carry cars or people up to 150 mph.

It really did sound amazing.

To drum up funding and buzz for the project, the company sold quirky merchandise like flamethrowers for $500 each, selling 20,000 units and raising $10 million.

The Hawthorne test site unveiled its first tunnel in 2018. It spanned 1.14 miles but didn’t have any of the vacuum tubes Musk had promised. Instead of a 150-mph platform that transported cars and people, Tesla vehicles operating at 40 mph with people in them just drove through the tunnels. While not quite as impressive as the initial pitch, it was still a success: it proved that automobile tunnels worked!

Unfortunately, automobile tunnels had already been proving successful ever since the Liberty Tunnel opened in Pittsburgh in 1924. TBC wasn’t exactly breaking any new ground here (no pun intended). Since underground Hyperloops were no closer to being a reality than above-ground Hyperloops—and automobile tunnels were already a thing—the only revolutionary aspect of tunneling Elon could tout was the cost: Traditional tunnel boring could cost as much as $1 billion per mile; The Boring Company would develop a tunnel bore that could do it for 10% of that.

In this endeavor, they were fairly successful…with a caveat: the way they were able to come close to boring a tunnel for 10% of the cost of a normal tunnel was by boring one that was 10% of the size of one.

TBC had definitely created a cost-effective tunnel; the only problem was that its cost-effectiveness didn’t actually solve any of the problems it was attempting to address in the first place: traffic gridlock. What these cheap tunnels did allow for was for single-file cars (Teslas only) driven by chauffeurs to travel at a top speed of 35 mph while praying to all the Gods of the Marvel Extended Universe that none of them ever broke down in the tunnel because there was no way to go around it in the carnival-ride-sized tube.

It was basically a niche concept with just a single operational tunnel thus far: a 1.7-mile loop connecting the Las Vegas Convention Center to Resort World Las Vegas, effectively solving a problem nobody knew they had in a town whose sole raison d’etre is creating problems for people.

I mean, the tunnel works—which is more than can be said for the Hyperloop—but finding something for it to do seemed almost like an afterthought. “Hey, we figured out how to make really tiny novelty tunnels nobody asked for for CHEAP! Does anybody want one?”

The one thing about The Boring Company that’s consistent with every other Elon endeavor is the comically overblown hype. The special boring machine SpaceX designed is called Prufrock. Prufrock 1 was unveiled in 2020 and was mostly used for testing. Prufrock 2 came out in 2022, claiming it could dig 1 mile per week, and that Prufrock 3, following in 2024, would be able to dig 7 miles per day.

As of 2024, Prufrock 3 was able to achieve 40-46 meters per day.

According to a former TBC employee, “Elon’s idea for the Boring Company was a good one. It just hasn’t been executed on.”

Neuralink

In 2016, amidst worries and fears from damn near everyone working on AI projects that AI was probably the most existential threat facing humanity, Elon Musk thought, Yeah, but what if we implanted AI computer chips directly into people’s brains?

Neuralink was born.

The company wasn’t widely known in the public consciousness until Musk went on the Joe Rogan podcast in 2018 and voiced his concern about the slow interface between human brains and computers. Since Rogan was the biggest podcaster in the world, society at large became privy to another cutting-edge, science-fiction-y innovation from the Mind of Musk and thought, “Yep, that’s Elon being Elon! I’m sure glad he’s on our side because nobody else could’ve come up with that!”

But, like the Hyperloop, the computer-brain interface idea had been around for a long time. The earliest known example was a paper published in 1973 by Jaques Vidal, a computer scientist at UCLA, titled Toward Direct Brain-Computer Communication.

Different researchers working off the ideas of Vidal were able to achieve some success in the field decades before Musk “came up with the idea” and got involved:

Philip Kennedy implanted electrodes into a human patient’s brain in 1996, allowing a paralyzed individual to control a computer cursor by thought.

By 2004, Matt Nagle, a tetraplegic patient, used a 96-electrode BrainGate implant to move a cursor and operate devices, a direct ancestor to Neuralink’s tech with its focus on implanted electrodes.

With those earlier advancements in mind, let’s be clear that when I say “Elon Musk founded Neuralink,” what I mean is that Elon Musk was the largest financial backer who co-founded Neuralink with 8 other specialists in the field who were already intimately familiar with the history of the technology:

Max Hodak - A biomedical engineer and entrepreneur

Paul Merolla - A former IBM researcher who worked on the TrueNorth neuromorphic chip

Vanesa Tolosa - A materials and neural interface expert from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Dongjin (DJ) Seo - An electrical engineer with a Ph.D. from UC Berkeley who developed Neuralink’s wireless systems and miniaturization.

Tim Gardner - A neuroscientist and bioengineer

Ben Rapoport - A neurosurgeon with a Ph.D. from MIT who focused on surgical techniques for implantation

Tim Hanson - A mechanical engineer and robotics specialist who helped design the neurosurgical robot

Matthew MacDougall - A neurosurgeon instrumental in translating the tech to human applications

These 8 superstars were gonna figure out the technology. Musk was just there to be the checkbook.

By July 2019, Neuralink had raised $158 million in total funding, $100 million coming directly from Musk. In another round of funding in 2021, the company raised another $205 million from Google Ventures and Peter Thiel’s Founder’s Fund. By 2024, Neuralink’s funding had reached $687 million.

To be sure, Neuralink has made some incredible, pioneering breakthroughs in recent years—a true testament to what science can achieve when you have basically unlimited funds to assemble a team of the greatest specialists and throw whatever dollars they require at the research they recommend.

Unfortunately, Elon’s self-described managerial philosophy of “move fast and break things” doesn’t translate equally well to all industries.

If you want to move fast and break things in the world of online payments, fine by me. If you want to do the same in the world of cars and rockets, have at it—it’s not my money going down the drain when things you didn’t intend to break get broken in the haste to move fast for fast’s sake, slowing down the end result. (Did Elon’s mom never read him The Tortoise and the Hare?)

But when we get into matters of the human body (and democracy), “moving fast and breaking stuff” runs into serious ethical (and legal) concerns.

Neuralink faced abundant criticism for animal welfare issues, with reports of over 1,500 animal deaths in clinical trials surfacing in 2022. That was 4 years after co-founder Ben Rapaport quit over safety concerns and left to go start his own rival firm, Precision Neuroscience. Since moving fast kills things when you’re experimenting with carbon-based organisms, Neuralink ran into a host of issues from the FDA, slowing down the company’s development enough to earn themselves a personal vendetta from the ever-petulant Musk.

According to Elon’s own Grok AI, “Elon’s real talent is less “inventing from scratch” and more “making shit happen.” He sketches bold concepts—throwing a bunch of money at ideas and allowing others to run with them.”

The problem is, he doesn’t even appear to be talented at the one thing he’s supposed to be talented at: playing conductor to his orchestra of talent. Accusations of poor management, unrealistic expectations, lousy communication, and insufferable working conditions have plagued him at every company he’s been associated with.

A 2022 Fortune article highlighted how Neuralink couldn’t meet Elon’s much-hyped deadlines because 6 of his 8 co-founders had already left the company for stated reasons that included: safety concerns, ethical issues, “lack of direction,” a “chaotic environment,” “dysfunctional management,” and inconsistent involvement from Musk.

Put bluntly, Musk’s greatest talent was being rich enough to surround himself with experts that he frequently managed so poorly that they left to go start rival companies.

It’s possible that Neuralink has come to realize the same thing PayPal did 25 years ago: Musk is a liability, not an asset. The strides Neuralink is making in human-computer advancements are with Jared Birchall as CEO—Elon currently has no executive position at all. Yes, the company’s doing pretty well…now that Elon Musk is out of the way.

In Conclusion

Since the Twitter takeover and rebrand was such a colossal fiasco that it’s become a cautionary tale in How To Destroy A Successful Business With Your Mere Presence that warrants its own deep-dive article, I’ll save that for another time.

The point here is that Elon Musk’s rock-star image as a real-life Tony Stark is based on extensive PR of Musk’s own creation. He caught a lucky break with Zip2 that he was able to parlay into an even luckier break with PayPal, which enabled him to fund whatever idea he came across that he thought he could pass off as his own to an undiscerning populace who desperately wanted superheroes to be real.

When it was announced Trump was putting him in charge of DOGE, all those Elon fanboys cheered the move because, FINALLY, we were getting the Greatest Business Mind Of The 21st Century to overhaul what we were being told was a system rife with inefficiency, abuse, and fraud.

The ugly reality of DOGE is that it’s a typical Elon gig: he’s swinging a wrecking ball without a clear blueprint for rebuilding—all while making outlandish claims and generating nonsensical hype about what DOGE is actually delivering.

The DOGE website is real. Go visit it. None of the numbers claimed add up. Most of the numbers cited are not examples of “waste, fraud, or abuse.” It’s a Hype Site delivering with the same precision as Musk’s grandiose assurances that he was going to colonize Mars by 2024.

He’s slashing federal jobs and budgets left and right, promising to save billions, with fans cheering him on like he’s single-handedly draining the swamp. They’ve bought the hype: he’s a billionaire visionary who built Tesla and SpaceX, so naturally it follows that he can overhaul Washington too.

But here’s the rub: smashing stuff isn’t the same as building it. Of all the companies associated with Musk, the only one that’s really analogous to the U.S. government is Twitter—fully established, working as intended, and profitable, but with plenty of room for improvement.

Operating under his go-to “move fast and break things” mantra, Musk came on board at Twitter and immediately fired everyone who knew how to do all the stuff he didn’t know how to do, forcing him to scramble to try to hire them back.

Sound familiar?

It’s funny in a tragic sort of way when it’s a bird-themed smartphone app. It’s terrifying when it’s the FAA, the scientists working on bird flu, and all our nuclear experts at the Department of Energy.

Musk notoriously overpaid $44 billion for Twitter, which has since seen its valuation plummet 80% under his “leadership and direction.” He moved fast and broke a bunch of stuff…but it wasn’t the stuff that needed fixing. The previous problems still remain. All Elon did was take a platform that had some issues and create more issues that he’s never figured out how to fix.

For my money, I can’t think of anything more fitting in America 2025:

The man elected president on the fame of his fake reality-show persona of being a brilliant businessman—a role he was only able to fit into his schedule by virtue of being so bad at business that American banks stopped lending him money and the only job he could get was a result of his Survivor producer buddy taking pity on him and letting him pretend to be good at business on TV—hiring the guy whose entire public persona of being a brilliant inventor who could build anything was an elaborate PR image crafted over the years by constantly taking credit for other people’s work to “fix” America.

Elon moved fast and broke stuff—the entire American government, to be precise. That’s what he does.

But fixing things is not what he does—it never has been.

So, now that all the breaking is done and it’s time to move on to the fixing stage, what is Elon doing?

He’s leaving.

Because the closest Elon Musk will ever be to Tony Stark is a 3-second cameo with Robert Downey Jr.

When Tesla was valued higher than all major German car manufacturers combined - combined - Audi, BMW, Mercedes Benz, Porsche, Volkswagen - yes, let that sink in for a minute - with lower qty. and sales volumes and (higher) US government financial support, it should have been a major big red flag! For any one.

But the US general public is so gullible.

I got to ‘working class parents’ and had to control my laughter so I could continue.